It sounds rather cliché, but relationships are funny things. They are very much their own breathing entities, shifting, changing, and living well past the efforts that we put into them. Over time, they become reflections of ourselves and the people we have encountered on our individual paths. With a little bit of luck (and a lot of hard work), these relationships demonstrate that we are creating a space that is better than we found it, richer for others who follow.

Janet has transformed so many people – students, colleagues, and, of course, friends. She has left marks of passion, temperance, and joy, to name just a few. The reflections below form evidence of her distinctive impact on each of us.

-Michael Leonard

Please contact Allen.Topolski@Rochester.edu if you would like to provide a submission to this portion of the site.

Conference

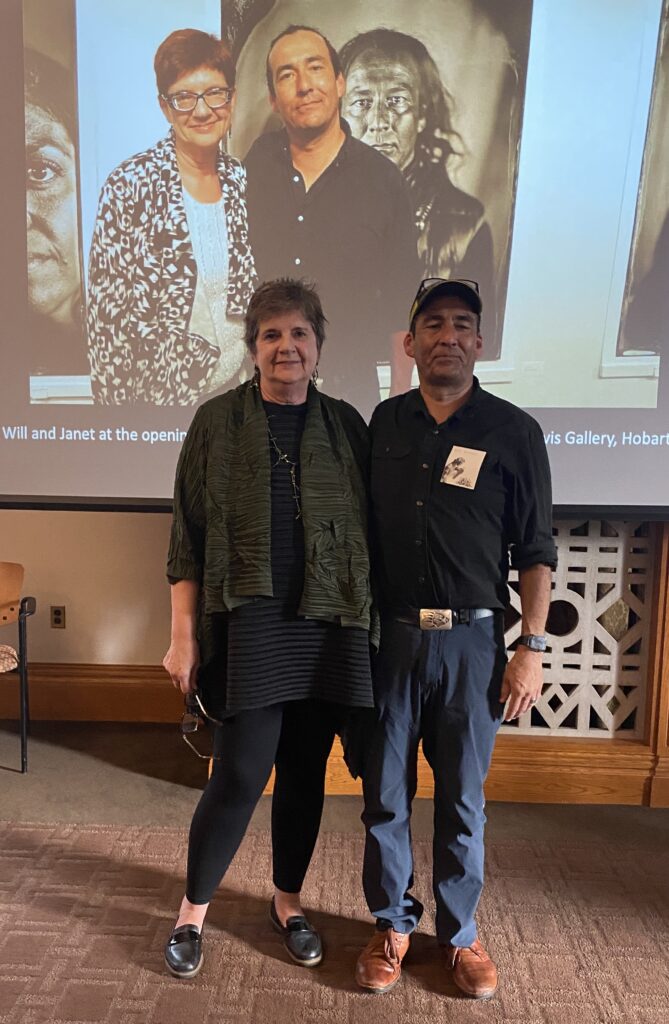

Arthur Amiotte

Martha Baker

I have always looked up to Janet. I have no choice: She is nearly 6′ tall, and I am (maybe) 5′ on a good day, sopping wet.

We met when she came to St. Louis to teach at the University of Missouri-St. Louis in 1979. She was full-time Ph.D., soon tenured; I, part-time with a master’s, just adjunct. She never looked down on me as the snooty delighted in doing. She taught art history; I taught writing in the English Department. Our offices were dove-coted on the 4th floor of Lucas Hall (management’s attempt to integrate disciplines). Not sure how she and I met exactly, but we glommed on to each other toot de sweet. Seventeen years later, I reluctantly helped tape packing boxes and threw her a small dinner party complete with a bouquet of Naked Ladies (lycoris squamigera) to say good-bye.

She wisely chose not to take her cactus to New York. I rescued it from under her porch, and it still grows at my house 20 years later.

In those St. Louis years, we walked together and dined together, and we sewed and read together even after I shifted from UMSL to the reporting staff of the St. Louis Business Journal. These pairings have continued over the miles throughout our long, cherished friendship, but we’re not identical twins. She drinks tea with lemon; I, diet and caffeine-free Pepsi. She loves dogs,

I’ve loved my cats. She talks funny Massachusetts; I speak eloquent Missouri. She went to fawncy Eastern schools; I attended public schools in the Midwest.

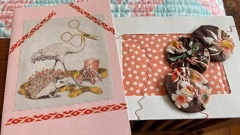

But we do share an awful lot. We detest being called “guys.” We have sisters — she’s the baby of three, I’m the second of four — with all the stories sorority involves. Janet helped me piece a quilt top,

and I hemmed the gorgeous jacket she’d fashioned. I admire her hand-crafted frocks. Because she machine stitches better than I, she generously lined my vintage tea cozy with Liberty fabric to complement my hand-embroidery.

She has cooked for me, vittles fit for a queen, for which I am so grateful as I am a baker in name only.

We toured Belgium, Florida,

Boston, Plimouth Plantation, quilt museums in Paducah, Ky., and Lincoln, Neb., and Falling Water in Penn’s Woods.

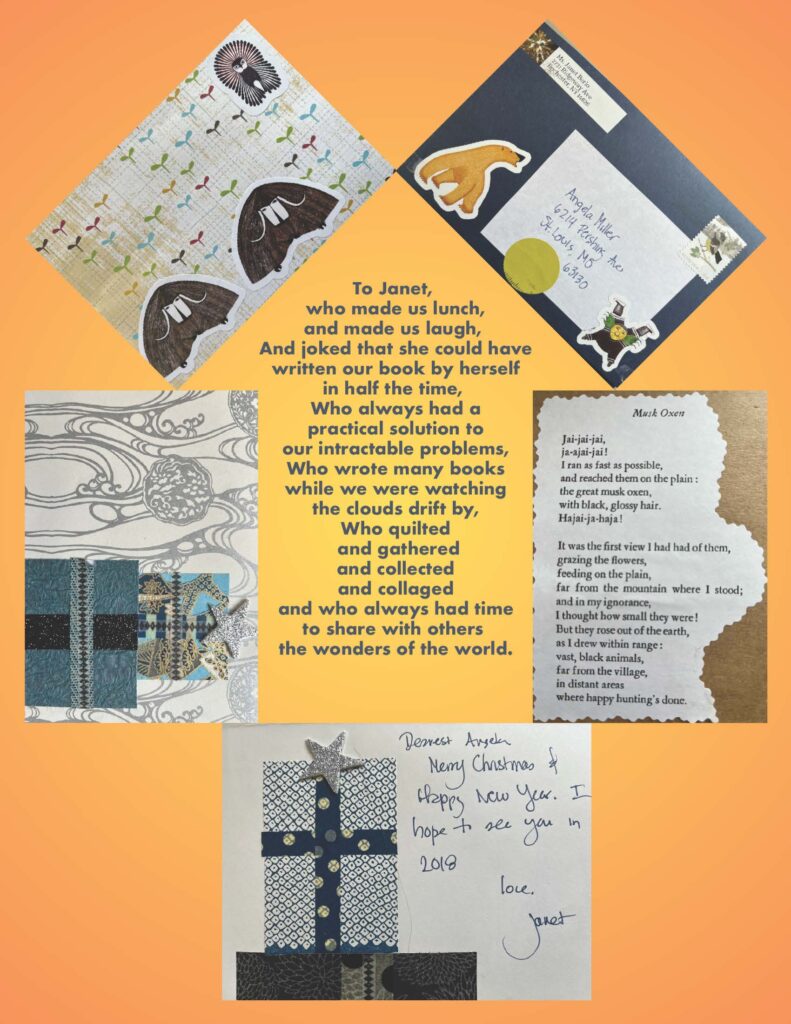

She stayed at my house in St. Louis and drove me to cataract surgery; I’ve stayed at her house in Rochester and giddily created cards at her dining room table. I’ve kept many of the hand-made cards she’s mailed to me because they are neat-o/keen-o.

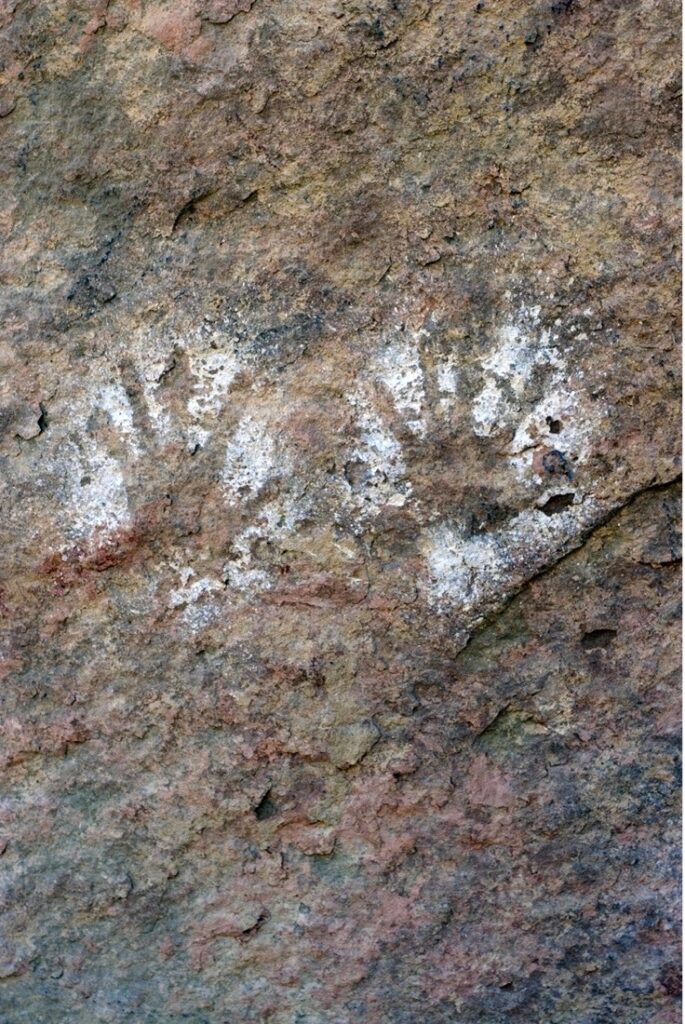

We’ve supported each other through heartaches and husbands. We supported each other’s professions — I so admire her pedagogy as teacher and mentor. We’ve bellyached and analyzed and commiserated with each other over the gravel in the groves of academe and over the infelicities of aging. We’ve edited together (I’m her “lie” v. “lay” resource) and written essays together. Her ruminations led to Quilting Lessons, which Publisher’s Weekly described as “intriguing and unusual”; I describe it as pure Janet. She introduced me to Western lore, especially to theretofore unknown Indian ledger books.

Here’s one of my favorite Janet Moments: once, when I visited her, I was reading Letters on an Elk Hunt by homesteader Elinore Pruitt Stewart. Stewart referred to laws around stealing and selling elk teeth. I asked Janet if she had any idea what the h-e-double-hockey-sticks that was all about. Janet rose up, swanned to her bookshelf, and brought back a magazine with an article about that very issue. Now, I thought, who else would not only know the answer to an esoteric question of mine but would have a resource to further inform me about elk teeth on dresses in 1915? In return, I add to her insight into odd women such as Elinore Pruitt Stewart, Zona Gale, and Marie-Madeleine Fourcade. She has praised my film and book reviews; I have praised her brilliant books (the kaleidoscope of Wild by Design swirls in my mind from my bookshelf).

She dances all over my house. The Christmas napkin holder she beribboned comes out in December. The block from an old friendship quilt that she augmented and framed as a gift when I was unceremoniously booted from UMSL’s teaching stable sits on my book shelf. A kimono quilt she designed hangs on my hall wall.

I have greedily attended her lectures. Her most recent lecture, at the St. Louis Art Museum, introduced her most recent book, Not Native American Art. There, sitting before her, awed in her audience, I was reminded that the woman whom I’ve traveled with, dined with, walked with, and wept with is an incredible scholar.

Janet Catherine Berlo is my dear, loyal, crafty, brainy friend.

I look up to her.

Martha K. Baker

Jose Bedia

Anna Blume

Tribute for Spring 2024

Janet Berlo

Professor Emerita, Department of Art and Art History

University of Rochester

From: Anna Blume

Professor of the History of Art

Fashion Institute of Technology, SUNY

In the spring of 1987 Janet was a visiting professor in the Department of the History of Art at Yale teaching a graduate seminar on Native North American Art. She engaged each of us heart and mind in that course with her depth of knowledge and her curiosity about all things tactile to the touch and haptic to the eye. It was and remains her profound kindness and humility in the face of offering so much that has stayed with me all these many years. She began as a teacher and mentor and through shared texts, stories, loves, and loses she became and remains a companion in the true sense of the word, someone to break bread with and to trust in this human world gone mad with cruelty. It is an honor to honor her as a wonderous, beautiful, beloved, creature – our most dear Janet.

Abigail Glogower

Quilting Lessons with Janet

Surely there was never anything in Janet Berlo’s contract or faculty work plan obliging her to open her home to graduate students for sewing lessons. But is anyone who knows her surprised that this naturally became part of her pedagogy, mentorship, and sisterhood?

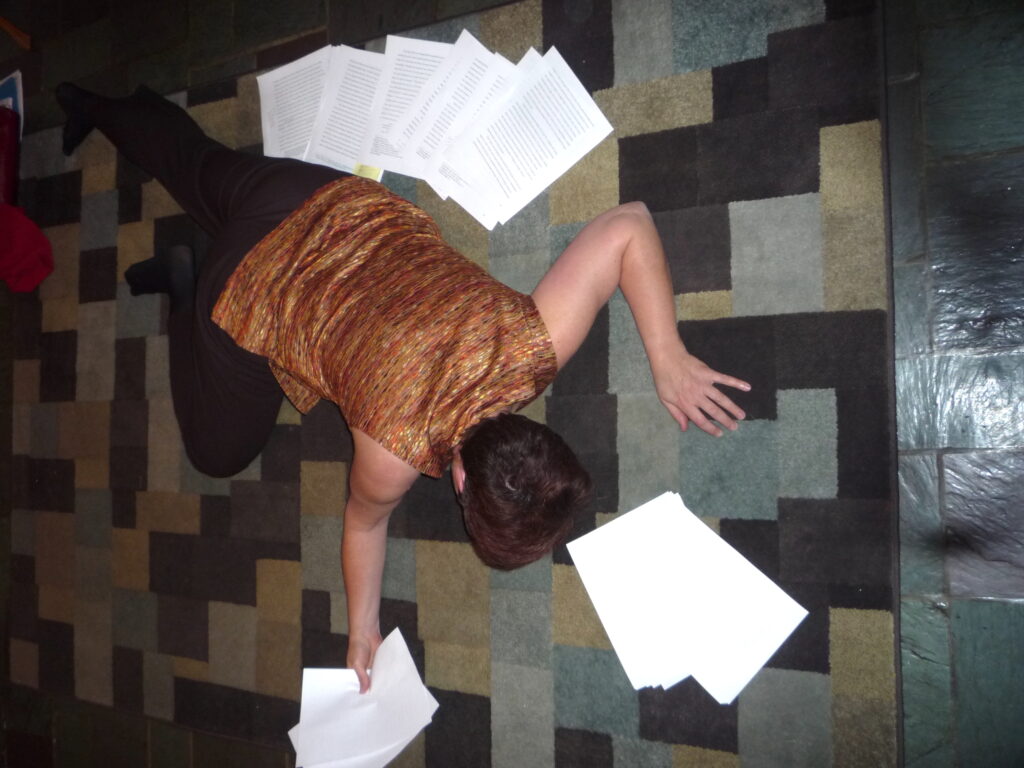

In May 2013, I was wrapping up my two years of VCS coursework and had recently read Janet’s 2001 memoir, Quilting Lessons. I was simultaneously inspired by and envious of her gifts. Who manages to reroute their writer’s block into another form of creative brilliance? Certainly not me, but obviously Janet! Clearly, inspiration won out because right then a timely extracurricular art-history project presented itself.

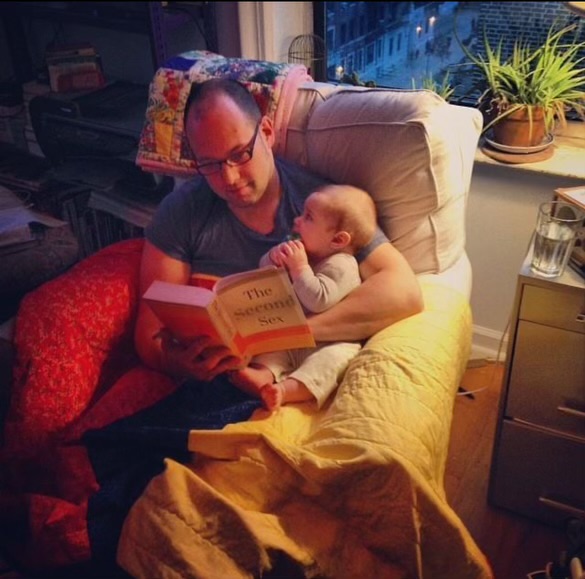

That spring, my good friend in the History Department, Clay Matlin, was immersed in his dissertation chapter about Barnett Newman and sublime tragedy in postwar American thought. When he and his artist wife, Sarah McDougald Kohn, announced they were expecting their first child that summer, I knew I had to make them a baby quilt and that it had to be a Barnett Newman baby quilt. But how? I hadn’t touched a sewing machine in nearly a decade, and let’s be honest, I was never particularly great at it to begin with. I’d pieced more tops than I had brought projects to full completion. The actual quilting part of quilting was a stage I’d barely gotten to.

I turned to Janet for help, and so began one of the most treasured experiences of my time as her student. Without hesitation (her email read, “We will have a splendid time”), she agreed to assist. That summer, she guided me through the entire project: fabric shopping at her favorite store; measuring, cutting, piecing, and pinning; and, finally, quilting binding. While we worked, we talked—about artists and writers, places we had visited, our upbringings, what we love, and what we won’t abide. I don’t remember what we talked about specifically so much as I just remember being together, having that kind of close but easy conversation amidst personally motivated applied learning. I knew even in that moment how incredibly lucky I was to be there, with a teacher who took a genuine interest in my interest and created an opportunity for something partway between instruction, collaboration, and keeping company.

In the end, Janet enabled me to fulfill my dream of a reversible Barnett Newman quilt: Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue IV on one side and Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue I on the other. To this day, I savor the pride and accomplishment I felt when we finished it. It was always an honor, joy, and comfort to be in Janet’s home, her “other classroom,” a place where I learned how to build and decorate a house filled with art, learning, quality snacks, and meaningful exchange, to be a better feminist, thinker, colleague, and writer— a magical place where even I, the clumsy sewer, could gain some quilting skills.

Thank you, Janet, for modeling such a holistic approach to lifelong learning and for nurturing not only our intellectual impulses but our creative and playful ones as well. Your impact on who I am today is larger than you can ever know. I love you!

Abby Glogower

VCS 2017

Research and Instruction Archivist

Mount Holyoke College

Photo Captions: Clay and Marsden Matlin, 2013, reading Simone de Beauvoir at home in Brooklyn, under their double-sided Barnett Newman quilt by Abby Glogower and Janet Berlo (shared with permission)

Katie Bunn-Marcuse

I can’t begin to explain all the ways that Janet has supported me over the years. I first met Janet Berlo at the Otsego Institute in 2002 where she gave me the first of many years of insightful advice when I was still a graduate student. When I became a faculty member in 2016 with a split position that was and remains a bit unrealistic, Janet really took me under her wing and provided yet more advice and strong admonition to attend to my writing, reminding me that no one gets tenure for answering email, only for publishing.

In the world of things-we-do-not-talk-about, like menopause, burn out, misogyny, or mental health, Janet dives in with straight talk and experienced advice and I have been so appreciative. But my most favorite support from Janet comes in the form of strongly worded (&*$!*) outrage on her behalf when academic bureaucracy (or any of the above unmentionables) rears its ugly head. Choice words of indignation are the gift that I didn’t know I needed.

A few other beloved memories:

2019 — In addition to being a talented art historian, Janet Berlo is a great chauffeur and caretaker! Here she is making sure I could enjoy Hearts of Our People even when I busted my knee. I wouldn’t have made it to the opening activities without her offer to make it work.

2017 – April:

Recipe for writing a book:

1) Know the wonderful Janet Berlo

2) Be invited to visit her for a writing retreat in Santa Fe

3) Janet will leave you in her house, in the country, 10 miles outside Santa Fe

4) Janet goes to her fellowship office in town. I have no car so she’s done her trick.

5) I have my computer, a stocked fridge, and Janet’s hound dog.

6) WRITE – because Janet wants to see some draft material this weekend. yikes.

7) Be grateful.

Kendall DeBoer

This is a placeholder tab content. It is important to have the necessary information in the block, but at this stage, it is just a placeholder to help you visualise how the content is displayed. Feel free to edit this with your actual content.

Kristin Dowell

Robert Foster

Janet is the consummate student-centered scholar-teacher. Serving on several dissertation committees that Janet chaired, I observed up close the careful way in which she advised her students. I of course mean “careful” in two senses of the word: Janet offered care and encouragement while at the same time devoting focused thought and attention to the work in question. I respected how Janet authorized students to resist the temptation of “doing theory” as an end in itself—Janet has a powerful BS detector—and I admired how she enabled students to achieve both conceptual and literary clarity. Janet’s criticism was always constructive and generative—a model of what we all wish sane academic interchange to be.

Janet was my personal guide into the world of scholarship on so-called primitive art when I was a bridging fellow with the Department of Art and Art History sixteen years ago. I was lucky to have Janet as an engaged interlocutor. Thanks, Janet, for joining me on the icy January road trip we took to a museum in Buffalo, which began at the gas pump with the revelation that my fuel door was frozen shut.

And thank you for your generous spirit, for always keeping others in mind—of which I enjoy an enduring memento. On a trip to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, you spotted a striking quilt hand-stitched by Mississippi artist Otesia Harper. The quilt featured eight squares. Inside of each square nestled a pair of iconic Coca-Cola bottles; along the bottom border of the quilt ran the words “Coke Covers the World.” Thinking of my research on the global spread of soft drinks, you sent me a snapshot of Harper’s quilt. I was later able to get permission to use an image of that quilt on my book Coca-Globalization.

It’s hard to give the perfect gift, because the perfect gift materializes aspects of both the recipient and the giver, aspects that both the recipient and the giver readily recognize. I regard the gift of the image of Otesia Harper’s quilt as perfect, and as a constant cheerful reminder of the larger gift of honest—dare I say authentic—collegiality that Janet has bestowed on me and so many others.

Harry Gu

There are many great things about grad school, but nothing beats the thrill of checking my mailbox. I am talking about the small cubbies in the copy room across the hall from the old admin’s office. Unlike those locked PO boxes you commonly see in post offices, my mailbox is simply an open cubby with my name on it. The Brits call them “pigeonholes.” Whenever I hear the term, I imagine a blue pigeon landing confidently in my designated spot, carrying a written note from a distant friend. Despite my constant checking, my box never contained anything personal. On a good day, I might find a white envelope with my paycheck in it. Most of the time, my daily visits amounted to nothing more than returned assignments and university spam.

But things changed after I met Janet. It was my second year in VCS. I was assigned as her Teaching Assistant for “Writing on Art.” I cannot tell you how elated I was when I received my very first hand-written note from her. And she continued leaving things in my pigeonhole until I graduated. They are always something small but delightful, seemingly unnecessary in the context of our roles: I, the student, she, the professor—a thank you card for a task fulfilled, an end-of-semester note wishing me respite, a gift card, or a beloved book with a handwritten endorsement. There is something whimsical about receiving things in the mail. It felt as though we were Sam and Suzy in the Wes Anderson movie Moonrise Kingdom exchanging mails to orchestrate our escape. It felt as though I belonged.

For the seven years when I was a graduate student, Janet was the only person who understood what the pigeonhole stands for in an institution of walls. It is not just an address, but also a hideout, a sanctuary, and an openness for friendship. She understood how the tangible presence of a written card helps us mark moments in life. As Bill Brown argues, things are the “sum of the world.” They relieve us from the weight of ideas. Handwritten cards, in particular, resist the commodification of relationships. They remind us of what the world is made of. They force us to confront the everydayness of life, which is always harder than one might think. Over the years, I have learned to do the same for my colleagues and students. I will always remember that Janet taught me how.

Jiangtao Harry Gu

Jessica Horton

The following is a lightly edited version of a reflection I offered upon Janet’s retirement in 2021, along with a few of my favorite photos of our writing retreats at Stephanie Frontz’s house in Santa Fe, 2011-2014, my PhD graduation in Rochester in 2013, and in the Virgin Islands in 2014.

I met Janet Berlo when I was an undergraduate student in San Diego in 2006. I was working part-time at the SANA Art Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to public education about the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas in San Diego. Our esteemed guest delivered a vibrant, funny lecture about the collages of her friend and collaborator, the Lakota artist Arthur Amiotte. There was not a hint of pathos in the art, nor in the words she wrapped around it—all was in vivid, living color. At the end, an elderly white man in the audience stood up, sobbing. “I can’t believe what we did to the Indians!” he wailed. Janet didn’t mince words, then or ever, but I recall admiring how she could still be generous while exasperated.

Sly wit, no-nonsense brilliance, uncompromising honesty, expansive kindness, surrounded by a riotous palette: These are some of the qualities I love most in my extraordinary mentor. The distance and dread sometimes conjured by the title, “dissertation advisor,” was absent from our relationship; after a few semesters of my coursework in Visual and Cultural Studies, Janet invited a deepening friendship and collaboration. We were happy holed up together in a snowstorm in Stephanie Frontz’s house near Santa Fe, hyped on chile and chocolate, co-authoring an article on contemporary Indigenous art and ecology for the Taylor & Francis greatest hits list. We were equally content with sparse words in the Virgin Islands, climbing impossible stairways in the rain, recovering from life’s traumas that rupture the gold-standard of “productivity” in academia.

In 2019, as I was mired in a scary bout of writer’s block in the wake of climate change disasters, the Trump presidency, and the stresses of completing the tenure-track, I reread the book that brought me to the University of Rochester in 2007. It was neither edition of Native North American Art (co-authored with Ruth B. Phillips), the eloquent textbook that has inspired generations of students, nor The Early Years of Native North American Art History: The Politics of Scholarship and Collecting, the foundation of graduate seminars I teach about the field, nor Spirit Beings and Sun Dancers: Black Hawk’s Vision of the Lakota World, the exquisite publication that altered how we understand spirituality and crisis. I reached in desperation for Quilting Lessons: Notes from the Scrap Bag of a Writer and Quilter, a slim trade book about depression and patchwork. “I begin to cry. Not big sobs. Just soundless tears, seeping from beneath my closed eyelids. I stalk into the living room and huddle miserable on the couch. ‘My academic life is over,’ I think to myself savagely. ‘I can’t even understand simple sentences anymore’” (1-2). Then, “Teal and midnight blue patterns, cobalt stripes, a sprigged hyacinth. Black with jagged ultramarine swirls. I would arrange them next to each other, add two, subtract one. … I see a vivid image of myself sheltered under a big quilt or surrounded by swaths of fabric, hiding within their protective coloration” (3). Descended from generations of women who piece for cover and pleasure, it is no wonder that I embraced Janet as chosen kin.

A couple of months into her retirement from teaching, Janet continues to shape the field of Native North American art with new books and exhibitions. Equally she takes up the tireless, unseen labor of reading others’ drafts (sometimes, incomprehensibly, the same day they are sent) and writing the kind of informal, three-sentence email introductions that make good things happen. “Grandma emerita, that is me!” she jokingly signed at the end of a recent email concerning the dissertation of a talented student of mine who she has never met in person. For most scholars of Janet’s stature, steering a bright new generation through an opportunity desert amid accelerating political and ecological crises is an alien task. Her inexhaustible gift as a mentor is the license to wordlessly cry and create, to pause and watch with wonderment “the unfurling of a new part of me” (2).

Jessica Horton

Aldona Jonaitis

Janet Berlo – scholar, friend, artist, gourmet, and animal lover

I’ve known Janet for decades and have always been in awe of her many incredible abilities. She is of course a brilliant scholar. Her warmth and love as a friend have no limits. During my darkest moments she supported and helped me heal. When some of us were young, we immersed ourselves in making art. But as we discovered art history, we chose to study, interpret, and analyze instead of creating art. But Janet never abandoned creativity – she remained an original artist of many works including colorful, dynamic textiles. She herself, dressed in imaginatively assembled clothing, is also a work of art. And, as anyone who has shared one of her meals can testify, Janet is also an artist of food.

What has brought us even more closely together is our mutual love of dogs. I’ve adopted some dogs over the years, and so has Janet. But she has, quietly and unassumingly, welcomed into her home damaged dogs who distrusted humans and rejected their love. One dog I met early in our relationship, Floop, a large Great Dane mix, had a difficult life about which I no longer know the details. I do remember that when she arrived at her new home she found stairs too challenging to climb. Janet worked with Floop and the next time I visited saw a peaceful and content dog.

Another more recent canine story is about Janet’s current dog, Cheddar. Janet had long wanted a Corgi and contacted a nearby rescue organization. They had a very troubled and detached female from a puppy mill and wanted to ensure a sympathetic placement. Many such organizations vet their potential adopters very carefully, often with a home visit. Not surprisingly, after they spoke for a while with Janet and learned of her experiences with rescue dogs, they asked her to come immediately and bring Cheddar home. This was one of the most difficult dogs to socialize and develop confidence that I’ve ever seen. She had no obvious connection with Janet, ignored everyone, and never wagged her tail. I saw Cheddar several times over the years and began to notice subtle changes in her demeanor as she – very slowly – began to understand that Janet loved her, and in this permanent home, she could relax and enjoy her life. The last time I visited, Cheddar was willing to sleep on Janet’s bed and to wag her tail. Thanks to Janet’s patience and empathy, Cheddar has transformed into a happy, trusting dog who loves and accepts love from her companion. For me, this achievement is a highlight of Janet’s accomplishments.

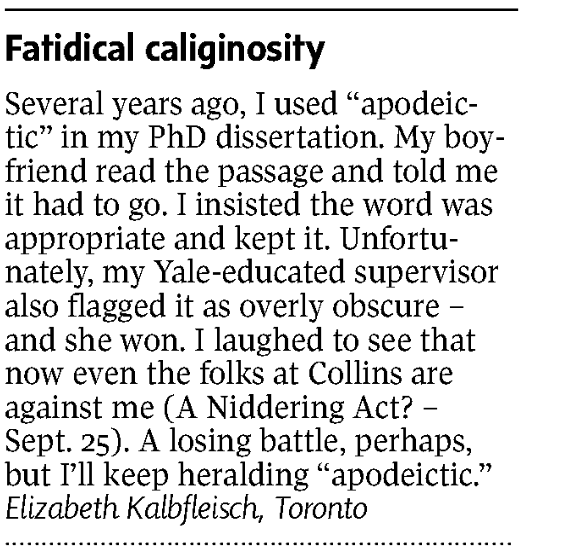

Elizabeth Kalbfleisch

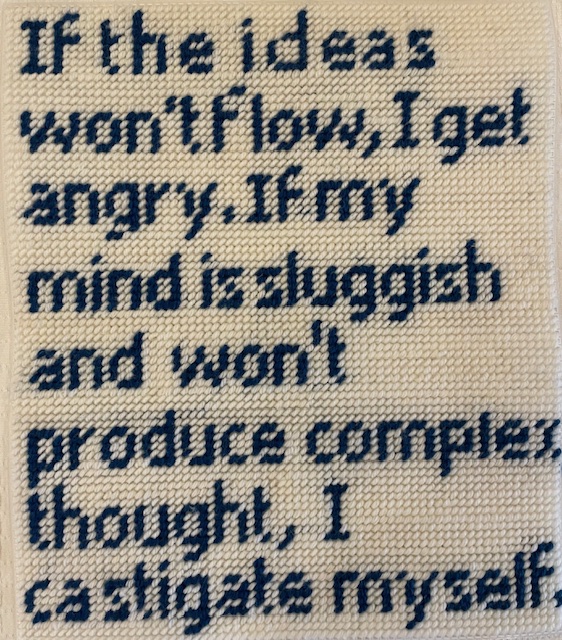

I arrived at the University of Rochester to study with Janet Berlo in 2001, the same year she published Quilting Lessons: notes from the scrap bag of a writer and quilter. Janet inscribed my copy, For Elizabeth, I’m so glad you’re here! – words warm and affirming and as I learned, so typical of Janet’s interactions with her circle. It was, of course, Janet’s stature in the field of Indigenous art that propelled me to the U of R; her scholarship in this domain shaped me intellectually and professionally in every way. Yet nearly twenty-five years after its publication, Quilting Lessons is the book I have returned to again and again as a piece of scholarly writing and as a kind of emotional companion I carried with me through several “lives” of my own. The way Janet surfaced the traditions and hidden stories in quilting gave me confidence as a researcher to delve into my own love of textiles and vernacular arts. Then, as now, I was awed by the unapologetic way in which Janet centered her own quilting practice alongside her scholarly work as an art historian. I was moved by the forthrightness of presenting life’s messiness–personal and professional–in such an unvarnished and beautiful way. Janet gave me a model for a “whole person” approach to intellectual life, before I had the words to describe such a thing. In the years I taught craft and textile history, I used Quilting Lessons as a prompt for a critical life writing exercise for students to weave together their own stories, learnings and art making. It will come to a surprise to Janet that later, I turned to Quilting Lessons as I navigated my own challenges and crisis of confidence, delving into it in a new way: the passages I had once marked with sticky notes now spelled out by my own hand in needlepoint.

–Elizabeth Kalbfleisch

Carolyn Kastner

We can all agree that Janet Catherine Berlo is an inspiring and extraordinarily generous scholar as well as a loving and compassionate human being. I share just one story as a testament to the inspiration, gratitude and joy shared by all of us within the powerful force field she exerts. In 2010, I invited Janet to write an essay for a catalogue for the exhibition I was organizing on the art and scholarship of Miguel Covarrubias, inspired by a single event three years earlier. She had introduced me to the Mexican polymath in an unforgettable conference paper she presented at the Native American Art Study Association. The subject of her paper was as interesting as her enticing narrative describing her research to authenticate a notebook of 80 drawings presented to her by an auction house as “Plains ledger art” from the library, not the art collection, of Miguel Covarrubias. From the beginning she set a tone of scholarly delight in her certainty that the source was not an Indigenous artist, followed by enchanting details of her investigative path of research into the provenance. The tale she unspooled for her audience immediately eliminated the possibility of a Plains artist as the source of the mysterious manuscript based on the violations of indigenous characteristics of style. Next, she trained her analysis on the anomalies of the iconography and format, nonindigenous influences that she identified as Art Deco and Mexican. Motivated by the manuscript’s location in Covarrubias’s library, not in his art collection, she refocused her research. Her own connoisseurship and knowledge of Covarrubias’s talents and cosmopolitan experience led her to attribute the drawings to the artist himself, who was based in New York City during the 1920s and 30s (where Art Deco art and architecture was highly visible), had extensive knowledge of the ancient codices of Mexico, and possessed the drawing skills to accomplish the hybrid feat she succinctly describes: “This is the ultimate in artistic bricolage: a sixteenth-century Aztec codex, as translated through the pen of a twentieth-century Mexican artist, in tribute to the nineteenth century artists of the American Plains, whose spare and economical graphic works he admired.” Only an art historian with a similarly astonishing range of expertise and curiosity could have parsed the hand of the maker so astutely. Her essay for the exhibition catalogue Miguel Covarrubias: Drawing a Cosmopolitan Line is a tribute to the artist and his scholarship on North American Indigenous art, a little known aspect of his extraordinary career.

But that was just the initiating event that led to more of her inspiration, scholarship and generosity. Before there was a catalogue, I had invited my colleague Khristaan Villela to be a consulting curator for the Covarrubias exhibition, because of his expertise in Mexican Modernism and the ancient cultures of the Americas. When I described my inspiration, he told me two astonishing personal details: As an undergraduate in the 1980s he had created a bibliography on Covarrubias, while studying with Janet Catherine Berlo. His essay traces Covarrubias’s research and publications on the Olmec, a culture first identified as distinct from the Maya through the artist’s connoisseurship along with his friend Diego Rivera. As I began my own research on Covarrubias, Janet suggested a current graduate student, Alicia Guzman, as an assistant. Like her advisor, Alicia’s scholarship was impeccable and became the foundation for my essay on Covarrubias’s transcultural modernism. Inspired, Alicia went on to write a seminar paper on Covarrubias’s 1939 Pan Pacific Maps, which became a brilliant catalogue essay that one reviewer identified as the strongest essay in our proposed publication. Curiously, Janet did not organize the exhibition or select the catalogue authors, but it is a fact that her scholarship and guidance created a team of collaborators over a period of 30 years. I conclude this tribute by declaring that I am not quite sure of the full extent of Janet Catherine Berlo’s powers, but I can declare with certainty they exceed ordinary time, space, and academic boundaries.

Carolyn Kastner, PhD, Curator Emerita, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Karen Kramer

I wanted to share a few reflections about what makes Janet Berlo one of the most remarkable, empathetic, brilliant people I’ve ever met, and also share a couple of photos from our journey over the years. I knew Janet’s scholarship, of course, before I knew her personally, having read of her many essays and books over the years on Native art collectors, ledger artists both historic and contemporary, the intersections of Native and American art, Plains quillworkers, Pueblo painting, oh I could truly go on. I had sat on several of her panels at NAASA over the years and watched with awe the ease at which she delivers her papers. She has always made it look so easy, whether in writing, presentations, or speaking off the cuff—this marriage of her deep engagement with the art, artists, and other thinkers. She speaks from the heart. She invites you to think with her, even if she doesn’t use those words. It was her wide range of knowledge of Native arts and her openness and spirit of partnership that inspired me to ask if, in 2008 or 2009, she would be an advisor on my first big solo museum project at the Peabody Essex Museum. Janet generously said yes, and stepped into a whirling dervish of a massive, multi-year exhibition and companion publication project “Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art” that opened in 2012. She connected me to artworks, artists, and scholars for the project (including her then-graduate student who is now our dear friend Jessica Horton) while writing an amazing essay and object entries for the book. She also mentored me by helping me to navigate difficult male egos, cultural sensitivities, and editors. Perhaps most importantly, Janet helped me articulate my own ideas and find my voice, which in turn began to build my confidence in ways that continue to shape who I am today. When I think of that Shapeshifting project, I remember the highs and the lows—my son was born, my marriage died; I got a promotion and had my first Boston Globe review by a Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic. Janet was there for all of it – to celebrate, mourn, listen, learn, talk, and eat lobstah! Over these many intervening years, Janet has remained a steady hand in my life. We’ve gathered in so many places and shared beautiful food with friends including in Santa Fe, Philadelphia, Marblehead, Williamstown, and Rochester. Janet has supported my endeavors in obtaining a doctorate and has subsequently talked me off Foucauldian ledges and across comprehensive exam pitfalls. Through it all, Janet has taught me what it means to be human-centered as a curator, scholar, and community member because she models leading with generosity, kindness, humor, humility, and creativity. I feel like I’ve pulled off the biggest hijinks ever because through working together, I’ve gained a sister, friend, thought partner, and comrade for life. I am so thrilled to toast to Janet’s well-deserved next chapter – retirement! – and cannot wait to plan our next adventure.

Karen Kramer

April 4, 2024

Heather Layton

Janet may not remember this but, when I started teaching at the UR in 2003, years before I found my feet and developed a comfortable understanding of academic culture, she asked me over for dinner. Imagine that. An astronomically respected, senior faculty member from the other side of the department who taught unrelated subject matter in a building I never visited, having the generosity, let alone energy, to make that invitation when she bore no further responsibility beyond knowing my name. I distinctly remember leaving that night having tried expensive prosecco for the first time and wishing that I had asked her more questions about her life, a wish that I would repeat upon leaving her home after each of the dinners that followed. This will be one of Janet’s many legacies: the ability and choice to not only see people, but to search for people to see. I am certain that I have inherited the luxury to carve my own space in academia thanks to Janet’s matriarchal trailblazing. She was practicing collaborative, shared power, compassionate, and intuitive approaches to teaching before it was the popular (and since proven most impactful) thing to do. For this, I am tremendously grateful. I extend all best wishes to Janet, in addition to buckets of optimism and an open invitation to come to my house for prosecco at any time. Much love!

Heather Layton

Angela Miller

This is a placeholder tab content. It is important to have the necessary information in the block, but at this stage, it is just a placeholder to help you visualise how the content is displayed. Feel free to edit this with your actual content.

Tara Najd Ahmadi

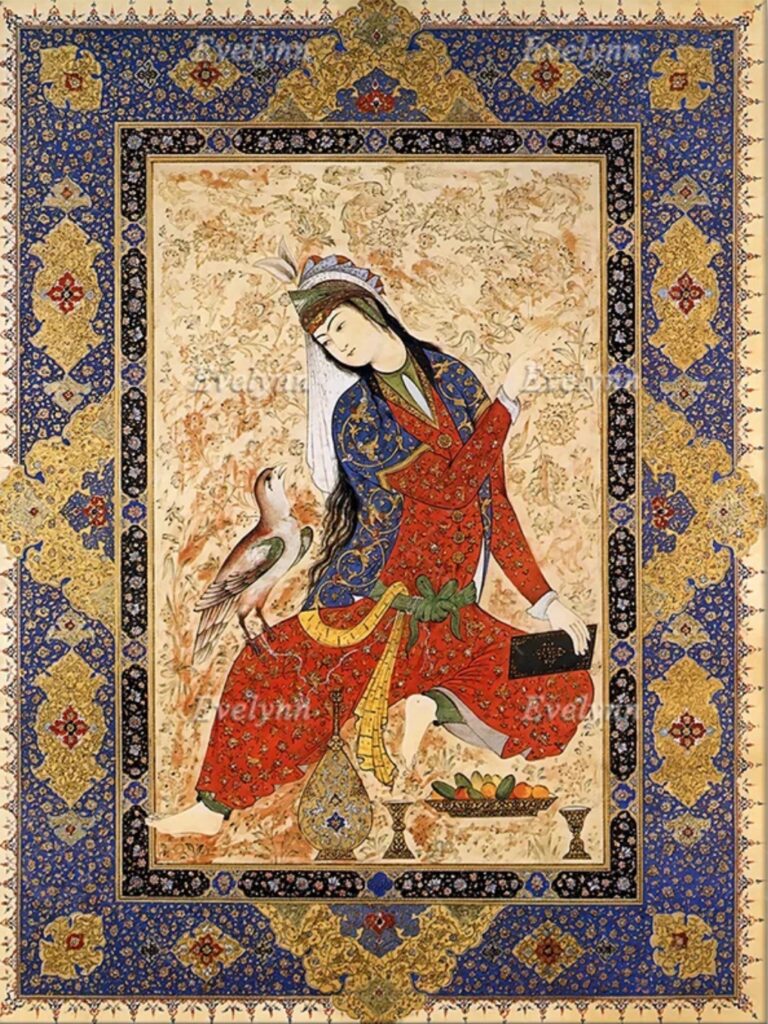

Kindness is a rare asset. It is a quality endlessly and eloquently celebrated in Persian poetry, from Rumi and Hafez to Khayyam and Saadi, as one of the highest virtues that intelligent individuals could strive for, along with the ability to build friendships and trust. The word that I am looking for combines these virtues and is perhaps best translated to English as something between “ease” and “familiarity”. In Persian, we have several words for that, such as “ashenayi”. It is an invisible social construct that allows for strangers, friends or lovers to communicate with each other in ease. It is an umbrella under which they can find refuge from a hostile temporal world; an environment in which they can exchange the most concise words of wisdom, the most beautiful words of appreciation, and the wisest humors.

I grew up in the rich shadow of Persian literature, both poetry and prose, and so I always, both consciously and unconsciously, looked for a version of this special “familiarity” in my social relations. After I arrived to Rochester and exchanged my first words with Janet, I felt the same form of ease and comfort. Janet’s words and gestures spelled genuine warmth and support of a kind that I had missed a lot; I saw Janet as a contented character from Persian miniature paintings of the 16th century, with women who sit in the center of the garden, read and drink wine and at times casually invite birds into conversations about the world’s most delicate mysteries since they are familiar with all languages.

Dear Janet, thank you for all the conversations, and your rare kindness. I miss you.

Chris Patrello

Anisoptera

The first time I went to Janet’s house, I was greeted by the large sculpture of a dragonfly affixed to a post where a basketball net should be. It is one of many artworks, objects, and ephemera that decorate her home. It’s strange to think about the ways in which we ascribe meaning to places, people, and things, and its even stranger that this dragonfly would come to mean so much to me, even if my first encounter with it seemed so insignificant. Janet’s mentorship imparted a fascination with the wonder of things.

I’ve been to Janet’s home for reading group meetings, meals, chores (mulching flower beds with Alex Marr), and any number of other occasions that are now escaping me. It has always felt comfortable to be at Janet’s house. Not just because she’s a gracious host, but being in her home has always felt safe. As one who has struggled with being vulnerable, Janet’s frankness, her openness, and her unique capacity to foster connectedness is a true gift to anyone who has had the privilege of knowing her and visiting her home. Janet made a choice to open her home to all of her students, and I never could have expected how important that choice was to me as both a student and a person.

In February 2018, I learned that my then-wife was ending our relationship a mere six weeks before my dissertation was due to Janet for one final review. It’s indescribably difficult to recall specific moments from that day, but I know that I emailed Janet to tell her what happened and to assure her that I was committed to making that deadline. She responded immediately. She said nothing of deadlines or extensions. She invited me to meet her at her home as soon as she returned from traveling the following day.

Again, details are hazy. But I can clearly remember Janet greeting me in her driveway, dragonfly overhead. She gave me a hug; a soul-affirming, cleansing embrace. I wish I could remember if Janet said anything to me in that moment. She very well may have. What I do remember is that she held me as I wept uncontrollably. I don’t know much about the stories associated with dragonflies or why Janet placed that dragonfly where she did, but I’m glad it was there. I look at them, and the world, differently after that hug.

Thank you, Janet, for teaching me how to look, how to write, and most importantly how to be authentic and vulnerable.

Chris Patrello

Assistant Curator of Anthropology

Denver Museum of Nature & Science

Jolene K. Rickard

My respect and admiration for Janet Berlo’s dedication for making the field of Native American and Indigenous Art History what it is today. Dr. Berlo was ahead of the curve on so many issues that are part of the methodological approach in Indigenous Studies today, but rarely has she been recognized in this cross-over space of Native American and Indigenous Studies. It is through her work that we are able to push the discussion of Indigenous feminism further. With care and gratitude for her contributions.

Jolene Rickard, Ph.D., (Tuscarora Nation citizen) Cornell University, History of Art and Visual Studies Department

T’ai Smith

For Janet Berlo

T’ai Smith

Looking over my acknowledgements to Bauhaus Weaving Theory, I realize there is a significant absence. I recount there a few details: about the mentor who schooled me in Marxist thought, about the one who convinced me that learning German wouldn’t be so hard, and of course about my supervisor, who was a fundamentally generous and astute reader… But I neglected to mention that it was Janet Berlo who encouraged me to learn how to weave. I recall sitting in her office, as she showed me some books; she suggested that in order to grasp the multiple dimensions of a woven texture, it would help to start with the cumbersome basics. To understand the craft, she implied, you have to do the tasks.

The evidence currently sits in a box on my bedroom dresser: two twills and an open (lace) weave, the first three samples I made between January and April 2003. They remind me of those snowy days in Rochester, driving to Mimi Smith’ classes at the Weaver’s Guild, where I was introduced to a whole new vocabulary and practice: about harnesses and shuttles, about yarn calculations and winding the warp, about the tie-up and threading of heddles, about selvages and the patience (I mostly lack) to do it all well.

It is almost comical that I absented Janet’s meaningful suggestion, given the book’s argument and its commitment to labor as the source of value. While most others in art history and visual studies at the time were bewildered by my topic, Janet took my budding curiosity about threads seriously. For that, I’m forever grateful.

Malaika Sutter

I met Janet during my master’s at the University of Rochester in 2019. I was immediately fascinated by her innovative teaching style and approachable, kind personality. I remember that all assignments had a clear, specific purpose geared toward the seminar paper or our career. Every choice was comprehensive and in our best interest. It was new to me that a senior professor could be so much in touch with her students. However, I quickly understood that Janet was no ordinary professor and that meeting her would fundamentally change my way of thinking, writing, and teaching both in and outside academia. Beyond her brilliant teaching and research, I learned from Janet that we are all, first and foremost, humans who carry a backpack of experiences and emotions with us. Janet was the first professor I could open up to about emotionally taxing situations during my studies, and she was the first person I could count on for support when I struggled with grief and mental health issues. Since she has become my dissertation supervisor, she has never put me under pressure; I can trust that whether I stay in academia or not, she will support me and always have the best intentions for me as a human being. That is an exceedingly rare trait in academia, but, as I said before, Janet is no ordinary professor. I will never forget how, during one of the most challenging times in my life, Janet made sure to contact me regularly, providing me with a supportive framework that enabled me to continue to work on my dissertation and which rekindled my joy and love for my research. I am so grateful for the mentorship, support, and, most of all, the friendship Janet has shown me over the years. I so am proud to be her Ph.D. student and to have been shaped by her research, teaching, and thinking.

April 2024, Malaika S.